Fighting to Stay Critical

A Talk at the Forum: Where Does the Critical Go?

Organized by

Mills Dray, Jonas Fridén Kihl, Onkar Kular and supported by the Design Unit, HDK Valand, University of Gothenburg and Göteborgs slöjdförening.

Mills Dray, Jonas Fridén Kihl, Onkar Kular and supported by the Design Unit, HDK Valand, University of Gothenburg and Göteborgs slöjdförening.

Forum Details

HDK-Valand, April 10, 2025

Röhsska Museum, Gothenburg

HDK-Valand, April 10, 2025

Röhsska Museum, Gothenburg

Introduction

This talk was shared as part of a full-day forum exploring what happens to critical practices after graduation—especially in the fields of design, craft, and architecture. The forum asked: Where does the critical go?

This talk was shared as part of a full-day forum exploring what happens to critical practices after graduation—especially in the fields of design, craft, and architecture. The forum asked: Where does the critical go?

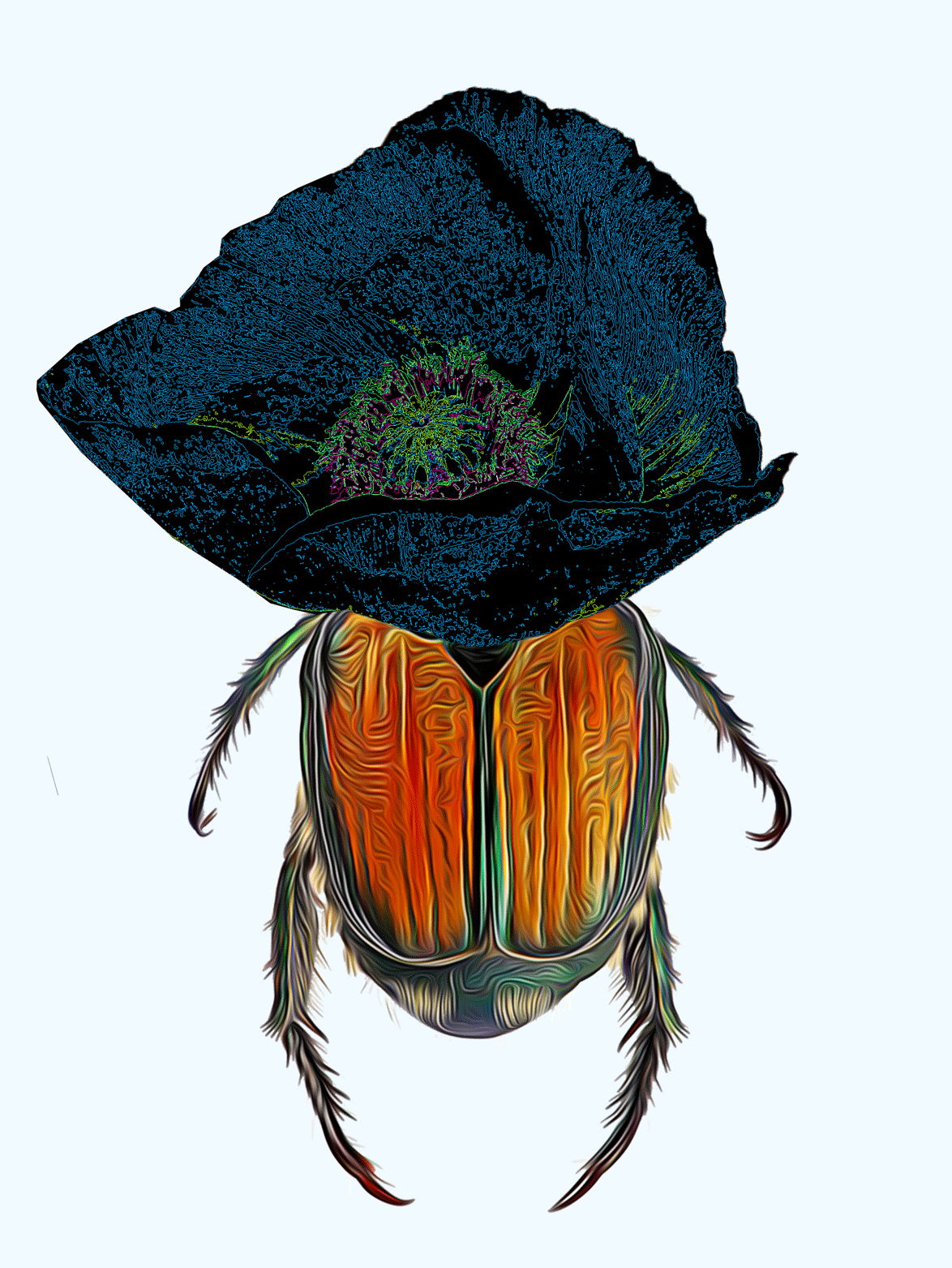

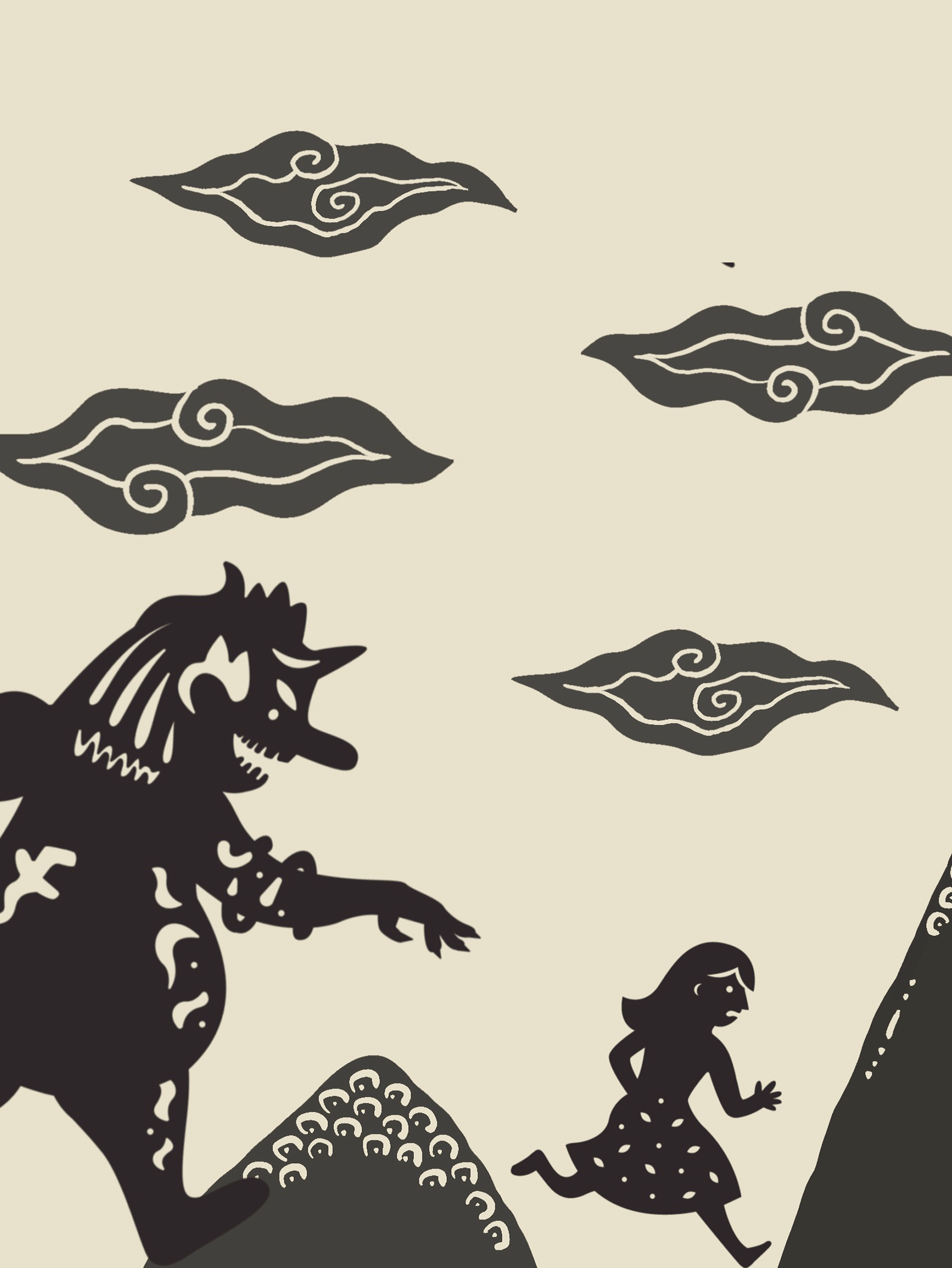

See this image?

Before I get into the story behind it, let me introduce myself.

I’m Leila Natsheh. I’m a 2019 graduate of the Child Culture Design MFA, a creative director, co-founder of Kotte (a collective I started in 2023 with Linn Rydell Montan and Omer Hingora), and a mother of two—Elias (almost 5) and Yasmeen (almost 1). I’m half Hungarian, half Palestinian. I grew up in Qatar and came to Sweden to study.

Since graduating, I’ve been trying to make something last—jobs, ideas, structures. And all of this while navigating parenthood, immigration, a new language (!), and the endless learning curve of Swedish bureaucracy. But more on that later...

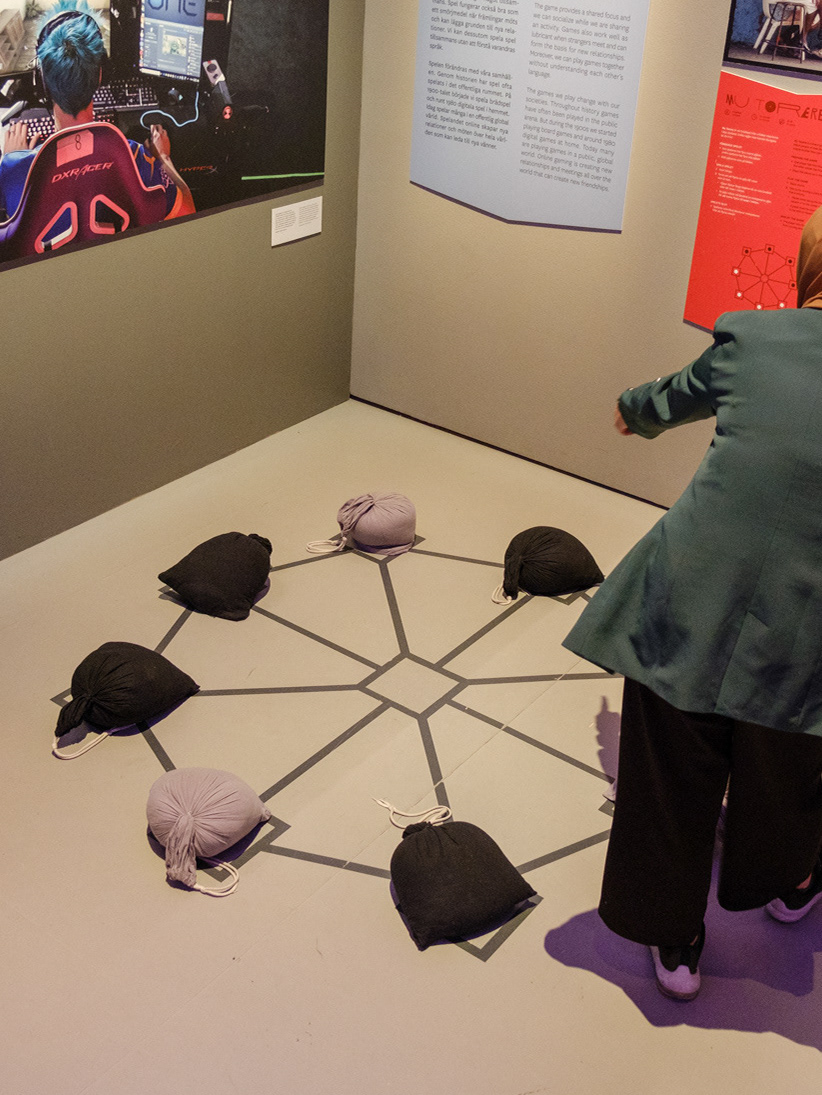

Back to the image

It’s slightly staged, but real.

You see me there—stressed, holding Yasmeen while signing papers for Kotte and prepping workshop materials (for an event I’m running voluntarily). Omer is next to me, knee-deep in a funding application while I describe a new idea for a project. Elias is being loud and playful with our equipment, as usual.

The table? A chaotic mix of tools: workshop stuff, documents, medicine, a laptop, and my paintings—meant to be a relaxing hobby but now just part of the mess.

This is what it looks like when a critical design practice tries to survive.

It’s not what you see on Instagram.

How did we get here?

To even reach this point, I had to spend 7.6 years figuring out how to write a project proposal. During that time, we estimate:

• 100,000 SEK lost in sick leave I didn’t know I was entitled to.

• 1 million SEK missed in parental leave, due to conflicting information as new business owners.

• 3,000 hours navigating Swedish organizational systems.

• 1 million SEK missed in parental leave, due to conflicting information as new business owners.

• 3,000 hours navigating Swedish organizational systems.

And that’s just what we’ve estimated. There's more we don't even know we're missing.

Why are we here?

• Because international students are expected to know how to navigate invisible systems.

• Because the education system assumes students will either "figure it out" or leave Sweden.

• Because there's no real bridge between learning critical design and sustaining it long-term.

• Because the education system assumes students will either "figure it out" or leave Sweden.

• Because there's no real bridge between learning critical design and sustaining it long-term.

A lot of the knowledge we needed was never taught—it was inherited, informal, or passed along by chance. You can’t expect someone new to absorb all of that, especially while managing everything else life throws at them.

So what can we do?

Here’s what I think we need, especially for Child Culture Design alumni:

• Alumni support structures that do more than track people.

• Alumni ambassadors who can guide students with lived, shared experiences.

• Support sessions throughout the program, not just at the end.

• Opportunities for collaboration between students and alumni-led organizations.

• Ensure stakeholders show up, especially at final exhibitions.

• Create structured introductions to networks, not just hope students find them.

• Alumni ambassadors who can guide students with lived, shared experiences.

• Support sessions throughout the program, not just at the end.

• Opportunities for collaboration between students and alumni-led organizations.

• Ensure stakeholders show up, especially at final exhibitions.

• Create structured introductions to networks, not just hope students find them.

And where do we start?

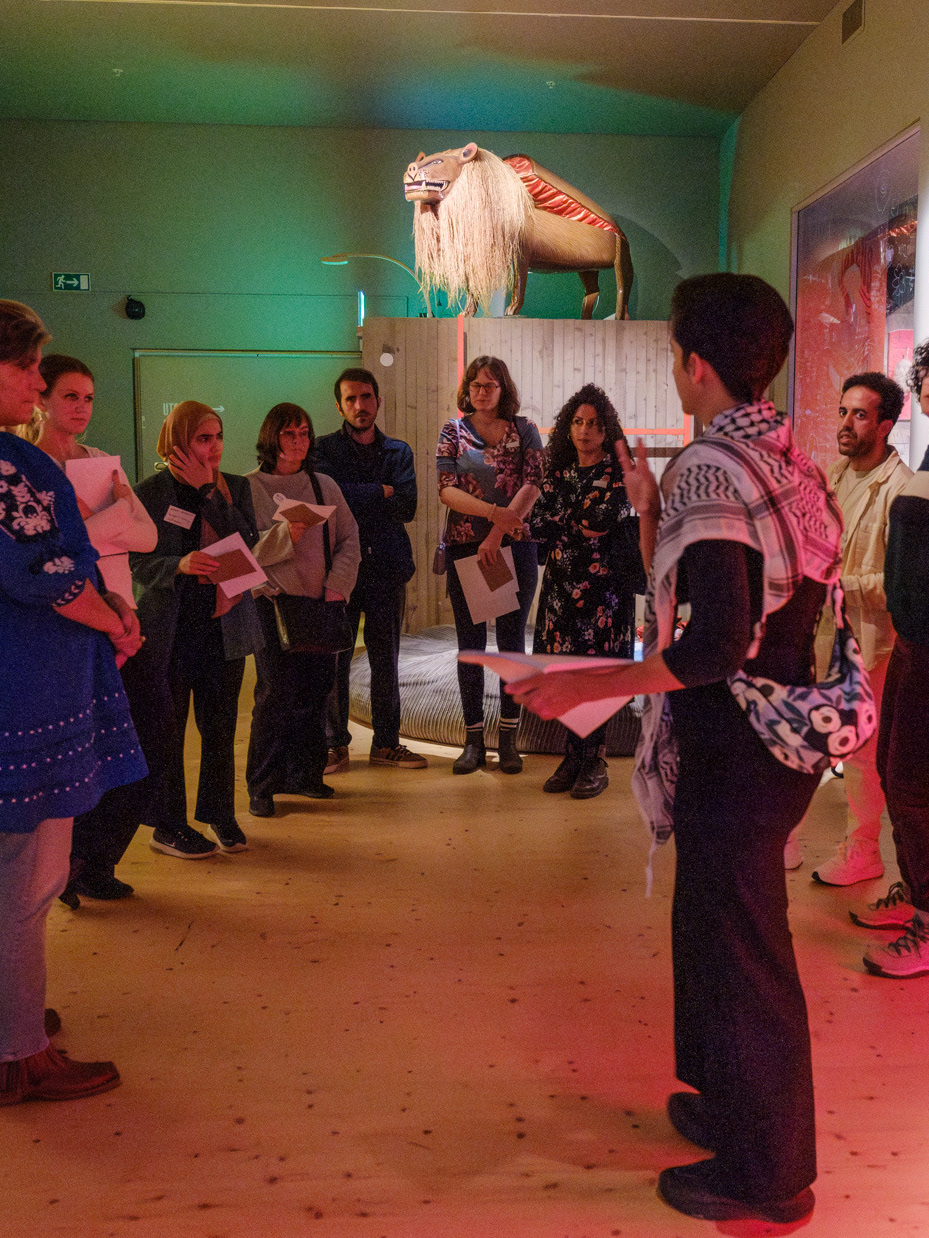

Let me tell you about Kotte.

Kotte is a non-profit. We work to diversify the cultural landscape with and for children, while promoting play as a right—for everyone. It’s a supportive space for overlooked talents: new mothers, internationals, community builders. People whose insight is too often dismissed.

We created Kotte because we needed a structure that didn’t exist. One that fights back against what I’ve described.

We’ve lived this struggle. We know what’s missing.

And we’re going to build it.

And we’re going to build it.

But we can’t do it alone.

Final words

The critical doesn’t just live in theory.

It needs to be supported.

It needs to be embedded.

It needs real, living structures around it.

It needs to be supported.

It needs to be embedded.

It needs real, living structures around it.

So I ask you—how can we build them, together?

Have thoughts and ideas on this topic? Let’s make them happen!